Picture This!

Let's Do The Twist

We can visualize the rotation of by by picturing a twisting effect along the axis of rotation. As the parallel components of are twisted, they maintain their overall length but twist and untwist. In this way, we can picture quaternions rotating points in 3d, enriched by our understanding of the algebra and of conjugation:

The point first appears as a "pure" quaternion, with no real component, before being multiplied by on the left. Then the intermediate product, , has a twist, with part of the magnitude of the parallel component stored in the real component. Finally, after completing the conjugation, the twist cancels out and is once again a normal point. The ability to move back and forth between viewing as a 3D point or a quaternion depends on conjugation cancelling out the twist.

Vector Operations

Cross Your p's and Dot Your q's

Notice what happens to the intermediate term, , when the angle is . (Reloading the page sets to ) The component parallel to the axis collapses entirely into the real component. Just like in 2D, a quarter turn captures the purely rotational behavior, i.e. the shift of one direction entirely into another. This is quite useful because it tells us the length of the component of that was parallel to without it being mixed up with the orthogonal component. ("orthogonal" means "right angle", coming from "rectus" meaning roughly "standing up straight") Similarly, the vector part of is nothing more than the component of that was orthogonal to to begin with, but rotated exactly a quarter turn such that it ends up orthogonal to both.

The twisted/real part is called (the negative of) the dot product, , while the vector part is the cross product, . These terms are so useful in and of themselves that they were separated out from the quaternion algebra and put to work as independent operations in vector and matrix calculus, partially to avoid the necessity of conjugation. Their utility comes from the fact that they can be used independently to compute and manipulate these components as desired, but this utility comes at the cost of potentially obscuring relationships that are more apparent within the quaternion algebra.

Paired Composition

The Algebraic Tag Team

We've demonstrated how points, temporarily represented as quaternions, can be rotated by conjugation, but how do we rotate rotations themselves? It turns out this is already in our picture! Consider what happens if we were to apply a second rotation, i.e. to conjugate the first versor with a second:

By re-associating the multiplications, we see that the composed rotation is nothing more than the product of two quaternions. Yet this is exactly what is represented, twice, in the visualization above! Its just that the quaternions and , which double as regular 3D points, are guaranteed (and required) to be pure, but we can still see all the behaviors involved in multiplying one quaternion by another by looking at the intermediate term . The fact that composing rotations boils down to a single multiplication is an important property that separates quaternions from pure angle-axis representations.

A bit of a sleight of hand has occurred, and its not unreasonable to worry that we are somehow overloading the elements in our algebra. E.g. on the one hand, we are saying that as a position the real component signifies a twist, and on the other hand, as an action it signifies stay. How we interpret it depends on whether or not the component is appearing as part of the rotation of a point or as part of the composition of two rotations. Furthermore, there is a mismatch in that a twist is coming out as , whereas stay is represented by . In addition to this, our imaginary vectors themselves seem to be performing double duty, both as axes and planes of rotation! It is up to us to keep the picture and the meaning of these operations clear.

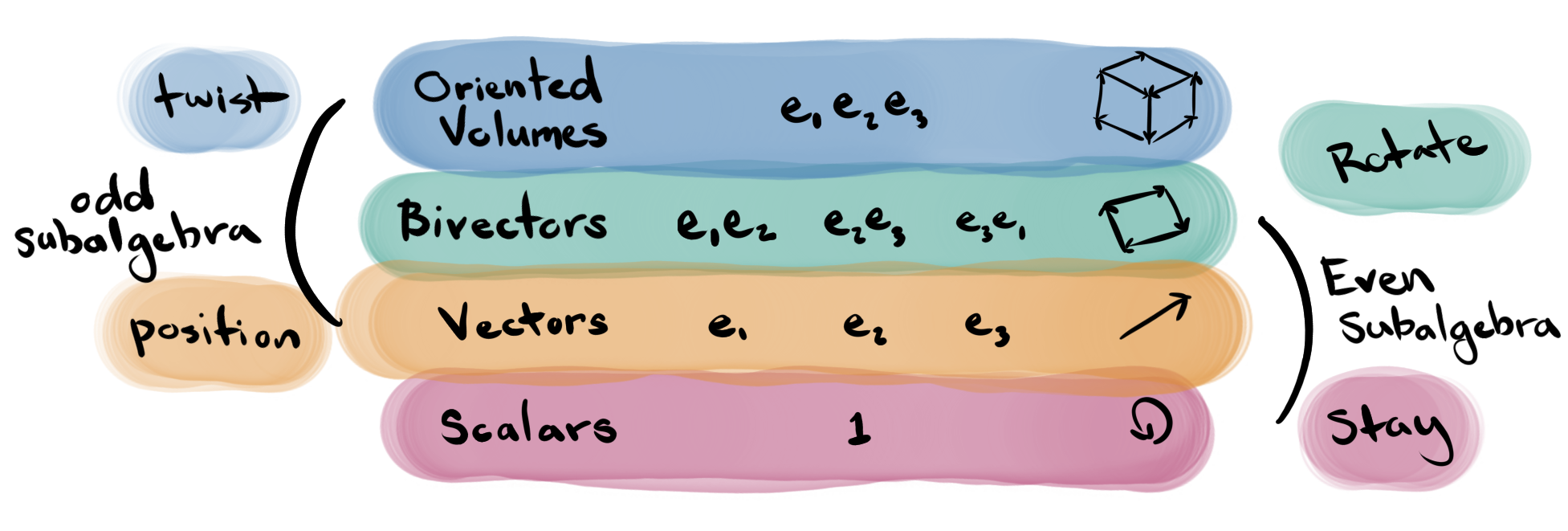

Lets finish with a brief consideration of what's called the Clifford or geometric algebras, which address these issues and more. These take as a starting point that multiplying a unit vector by itself should give back the identity, , rather than , while at the same time keeping the anti-commutative machinery necessary to permit rotations. But didn't we say this was impossible, and that the corresponding algebra would collapse? Only if we require that the axes be able to perform double duty as the planes of rotation! In the geometric algebra these are separate objects. The geometric algebra once again doubles the total number of elements in the algebra, and contains not only real numbers and vectors, but also oriented areas and volumes.

In the Clifford/geometric algebra there is indeed a difference between the stay-in-place and twist behaviors that is not explicit in the quaternion algebra alone. In fact, they are different types of objects! When composing rotations, the only terms involved are those of the even subalgebra, in 0 or 2 dimensions. These are the scalars and oriented areas (bivectors), meaning stay and rotate respectively. However, when rotating a point, the odd sub-algebra, containing 1 and 3 dimensions, is involved. In this case the intermediate term in the conjugation that results from rotating in place is an oriented volume, not a scalar. Once this oriented volume is "wound into being" it can be "unwound" along any axis. I.e. its not necessarily aligned to any particular direction or plane of rotation. This detail, however, is irrelevant in the context of rotating 3d points, in which multiplication always occurs in the context of a conjugation.

When switching our interpretation of quaternions between rotations and positions, what we are doing in terms of the geometric algebra is switching between dual subspaces. That is to say, the axis of rotation is in a dual subspace to the plane of rotation, where together they fill the entirety of 3D. Similarly, the "twisted" oriented volume component forms a dual subspace with the scalar component, together "filling" 3D space. The quaternion variables are only able to carry these complementary meanings because of this dual relationship, and its up to us not to mix up the interpretations. The geometric algebra, however, disentangles these behaviors and can give a clear and direct picture all the way through, but at the expense of doubling the number of elements in the algebra!

The End

I hope you enjoyed exploring these wonderful mathematical objects with me. If you have comments, suggestions, critiques, or requests, please send me an email!

- Kruft